Decolonising museum practice: new insights for government

How a Northland iwi’s partnership with Auckland Museum provides a possible model for government

Te Papa Museum, Wellington (photo by Te Papa).

A true willingness to partner with iwi would totally transform New Zealand's public service says Ngāti Kuri board member Sheridan Waitai.

But she’s not holding her breath.

“After all these years, we’re still trying to forge a relationship with the Crown as an iwi. It’s sad, really. But we’re just not getting very far. There doesn’t seem to be a true willingness. So we’ve simply got on with living our aspirations with support from other less conventional partners,” Sheridan tells me on a visit to the Far North.

Ngāti Kuri and the WAI 262 claim

Ngāti Kuri is an iwi of approximately 6,500 people.

Their rohe covers one million square kilometres of land and ocean, extending from Maunga Tohoraha (Mt Camel) in the south, to Te Rerenga Wairua (Cape Reinga) in the north, to the off-shore islands of Manawatawhi (the Three Kings Islands), and up to Rangitahua (the Kermadec Islands).

In 1991, Ngāti Kuri was one of six iwi who lodged a Treaty of Waitangi claim called the WAI 262. The claim made a case to change the way the country’s flora and fauna are managed and give Māori greater control over things Māori such as indigenous plants and animals and other taonga, such as mātauranga Māori or indigenous knowledge.

It was the first whole-of-government claim and resulted in a lengthy report published in 2011, Ko Aotearoa Tēnei, documenting Māori taonga species and how they should be protected. Sheridan’s grandmother, the late Saana Waitai-Murray, was one of the original claimants and the only claimant alive when the Crown finally delivered its report.

“She dedicated her life to that claim. But, look, it’s now another eight years down the track, and we’re still awaiting a formal response from government.”

Northland, New Zealand (image by Jacqui Gibson).

Partnership with Auckland Museum

The silver lining in all this, however, says Sheridan, is the iwi’s relatively new partnership with Auckland Museum, initiated as a way to breathe life back into the WAI 262 claim and realise Ngāti Kuri’s post-Treaty settlement goals.

One of the iwi’s primary goals is to completely rejuvenate their lands and oceans, bring back taonga species, and transform 33,000 hectares of their rohe into an eco-sanctuary, protected by an 8.5 kilometre predator-proof fence.

“Our partnership with Auckland Museum’s natural science team is absolutely central to achieving our aspirations as an iwi,” says Sheridan.

To date, the partners have developed a shared-work programme, which continues long-term land and ocean studies and kicks off new studies such as a stocktake of Ngāti Kuri taonga species.

To take the workload off Ngāti Kuri and to co-ordinate the scientific research within their rohe, Auckland Museum now brokers contact between Ngāti Kuri and New Zealand’s scientific institutions such as NIWA; Landcare Research; and Auckland, Otago, Massey, and Canterbury universities.

Museum staff regularly run “bioblitz” events in the Far North, teaching Ngāti Kuri kids how to survey pest and taonga species and monitor the health of ecosystems such as freshwater streams.

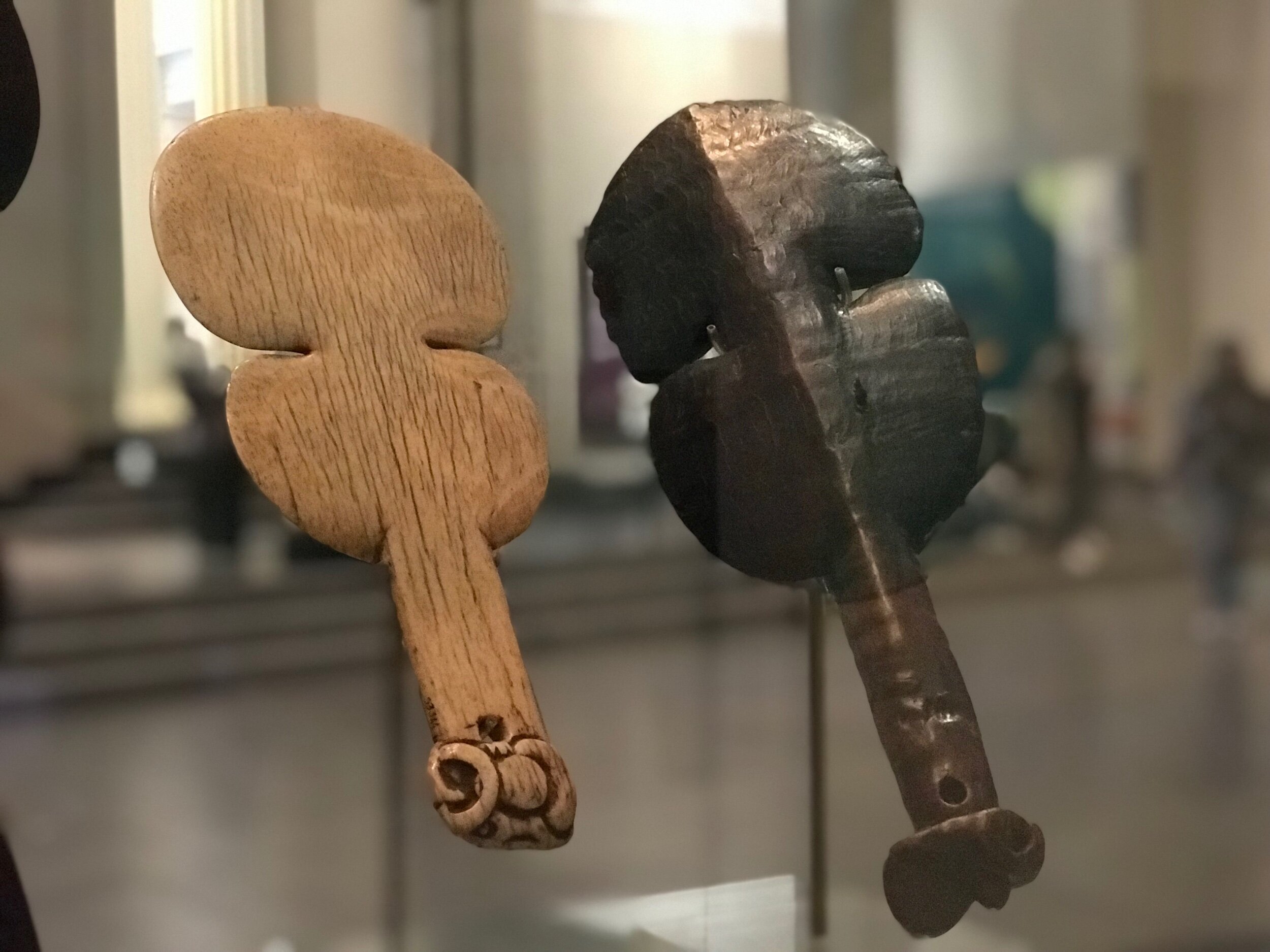

Ngāti Kuri objects that are in the natural science collection are now catalogued in both Western scientific and mātauranga Māori terms, while new exhibitions exploring the natural sciences from a Ngāti Kuri worldview are in train.

Early in the partnership, koiwi (human remains) belonging to Ngāti Kuri stored in the museum were returned to the Far North.

Auckland Museum Head of Natural Science Tom Trnski says the four-year partnership has completely transformed the way his team works with Ngāti Kuri. But it’s also done wonders for the museum’s understanding of how to work successfully with iwi.

“I’ll never forget the day Ngāti Kuri approached us. They basically said: ‘Look, we’ve had your scientists coming up here since the early nineteenth century and we’re sick of the one-way relationship. You seem to think it’s okay to do your work and then disappear, taking your knowledge about our lands and oceans with you. Well, we’re no longer okay with that. We want to form a true partnership with you. We want a relationship that’s reciprocal, where you support our aspirations and we support yours.’

“Honestly? My first thought was, ‘Holy moly, how are we going to bypass the usual Crown-led approach and navigate our way through this? But we found a way. And, really, that ultimatum from Ngāti Kuri was the start of a whole new era for the relationship.”

Museum practice in New Zealand Museums Aotearoa Executive Director Phillipa Tocker believes the Ngāti Kuri partnership with Auckland Museum is unique for putting science at the centre of their relationship.

However, New Zealand museums are generally ahead of the game when it comes to partnering with Māori and embracing biculturalism. Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand’s only national museum, is a case in point.

“These days, New Zealand is teaching the global museum sector an entirely different way to carry out its work – examples include the repatriation of human remains and the status of mātauranga Māori in our research work and exhibitions,” says Phillipa.

“It’s part of a bigger international shift. Museums have moved from being the ‘keepers’ to the ‘storers’ of taonga and knowledge. We don’t so much ‘show’ visitors objects as encourage them to ‘experience’ them. And we’re less ‘knowledge centred’ and much more ‘people centred’.

“Saying that, we’ve still got a long way to go. We don’t have nearly enough Māori staff in our sector, for example, and best practice is patchy. Museums Aotearoa is the parent body of approximately 470 museums. As a general rule, I’d say it’s the bigger museums that are embracing bicultural practice and leading the way.”

Decolonising museums

Te Papa Kaihautū (Māori Co-Leader) Dr Arapata Hakiwai agrees.

“Museums worldwide are decolonising their practice – and they’re looking to institutions like Te Papa for ideas on how to do it. Just this year, I spoke at a European Union session at Cambridge University on Te Papa’s bicultural approach.

“Two years ago, our chief executive and I shared Te Papa’s experience at the Australian and New Zealand School of Government. There’s a real acknowledgment that museums, just like other public agencies, must change.”

Today, Te Papa has a wide range of policies and practices to support its work with iwi, says Arapata. For example, the museum has developed more than 20 individual relationships with iwi.

Every two years, Te Papa staff meet iwi at regional hui to discuss iwi aspirations. There’s a four-year Iwi-in-Residence programme, and Te Papa staff are frequently involved in Treaty discussions.

“We started down the path of decolonising museology years ago; before we even opened. We were determined we weren’t going to perpetuate a practice that doesn’t serve our nation’s interest.

“We said to ourselves, ‘Why shouldn’t we create a unique, bicultural museum practice? Why should we blindly adopt what other museums are doing when we know it disenfranchises and disempowers and is really counter to creating meaningful relationships?’”

Arapata says museums such as Te Papa and Auckland Museum have plenty to teach New Zealand’s government agencies looking to develop new ways of working.

“But, to do this work, you have to be prepared to interrogate the old ways. I’d say the journey towards biculturalism, especially as a nation, is ongoing and potentially very difficult because, at the end of the day, it’s about sharing power and authority.”

Public sector change

Te Arawhiti Chief Executive Lil Anderson agrees the journey can be tough, but she insists New Zealand’s public sector of more than 350,000 people is finally ready to change.

“It’s taken us this long – about 35 years – to repair the broken relationship through the Treaty process, but we’re ready now,” says Lil, who set up Te Arawhiti, the Office for Māori Crown Relations, last year.

And while her office is coming up with some of the answers, others are being found in successful iwi partnerships like the one Ngāti Kuri shares with Auckland Museum and those fostered by Te Papa, she says.

“What’s clear is that central government needs to follow suit. We need to completely rethink the way we engage with iwi. I’m talking about everyone from leadership to policy makers to people delivering services in the regions.

“We need to engage more, and we need to change the way we engage. We need to explore the institutional racism and unconscious bias within our agencies. We need to rethink our organisational processes – from the way we govern to our hiring practices. And we need to identify the ingredients of successful partnerships and embed them in our agency practices.”

Right now, several new ideas about how to do that are being developed for discussion with public sector chief executives and the Minister for Māori Crown Relations, Kelvin Davis.

Travelling to Kaitaia, for example, to talk to people who are living in poverty face-to-face and involve them in policy solutions might become standard practice for policy makers in the future, says Lil.

So too might all-of-government professional development centred on achieving recognised levels of cultural competence.

In July, Te Arawhiti launched a new online portal called Te Haeata outlining the Crown’s Treaty commitments to Māori. There are around 14,000 commitments in total.

Next year, the portal will become open to the public and give everyone a way to track an agency’s progress towards meeting its Treaty commitments.

Meantime, Te Arawhiti has started documenting the Crown’s iwi partnerships (and what’s being achieved within each one) as another way to track progress and share good practice.

They recently assigned Te Puni Kōkiri as the lead agency to work with Ngāti Kuri and other agencies to finally resolve the WAI 262.

“How would I rate the Crown’s relationship with iwi today?” asks Lil.

“I’d probably give it a four out of 10 to be honest. I’d be wrong to say we’re starting from zero, because there are a few amazing pockets of success out there. Yes, we have a long way to go – but in five years’ time, I hope we’ll at least double our current score.”

This story first appeared in the Public Sector Journal.

The writer would like to acknowledge the Aotearoa New Zealand Science Journalism Fund, sponsored by BioHeritage Challenge, Ngā Koiora Tuku Iko, for support to travel to Auckland and the Far North for this story.